ABOUT THE ARTIST

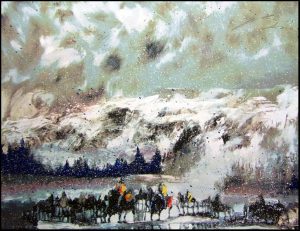

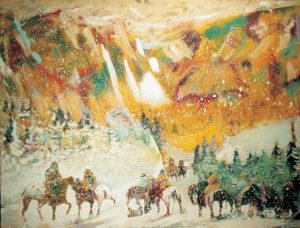

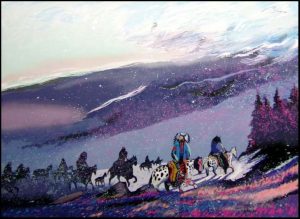

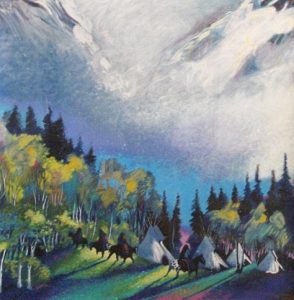

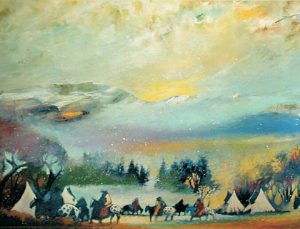

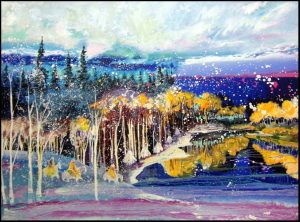

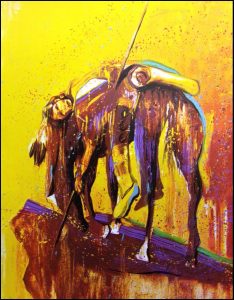

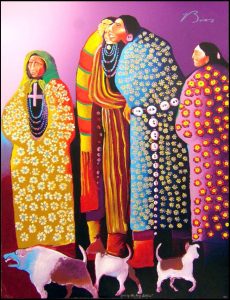

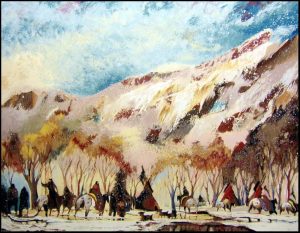

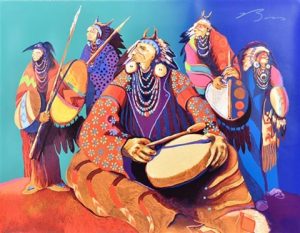

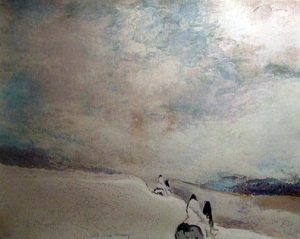

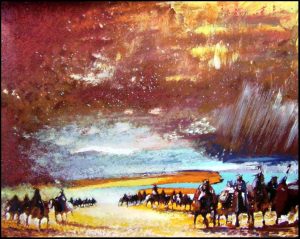

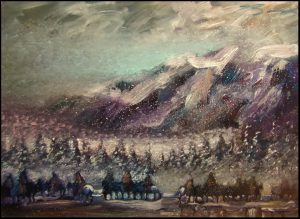

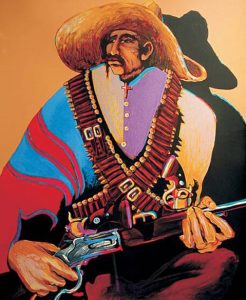

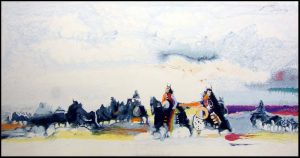

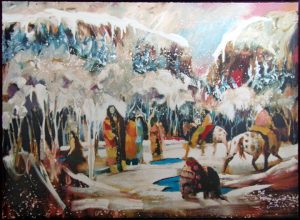

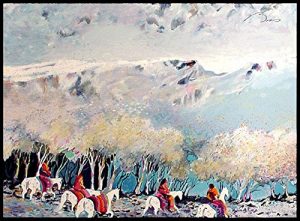

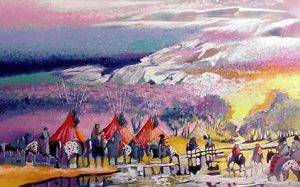

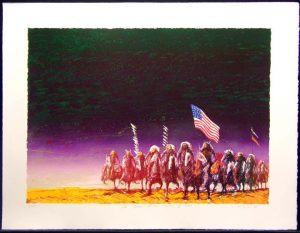

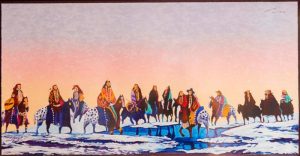

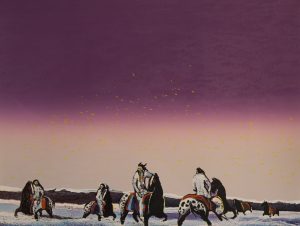

Earl Biss (1947 – 1998) was a profound contributor to the explosion of Southwestern Art in the last half of the 20th century, and particularly to the rise of contemporary Native American Art. His compelling portraits of Plains Indian horsemen, his phenomenal grasp of the medium of oil painting, and above all the sheer exuberance of his palette and brushwork earned him a place in the history books of modern art. He was, according to one Southwest critic and collector, ‘The greatest colorist of the 20th century.’

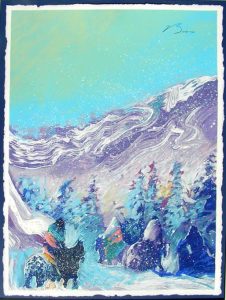

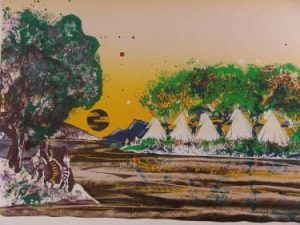

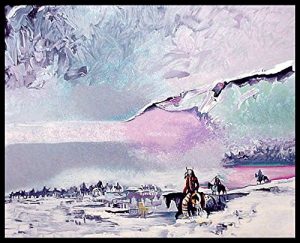

Born in Reston, Washington and raised by his grandmother on the Crow reservation in southern Montana, Biss was an enrolled member of the Crow Nation and given the Indian name ‘Spotted Horse’ by the tribe. He found inspiration for his works in tribal legends and histories learned from the elders, and in the sweeping landscapes of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains.

Biss was a central figure in the ‘miracle generation’ of students at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe in the 1960s. When Earl and his fellow students – which included Kevin Red Star, T.C. Cannon and Doug Hyde – arrived at IAIA, western art was focused on cowboys and landscapes, while Native art was stylized, linear and depictive. (And often produced for the tourist market.)

That perspective was too narrow for Biss, who studied painting with Fritz Scholder, sculpture with Allan Houser, jewelry and design with Charles Loloma and architecture with Paolo Soleri. Inspired by these teachers, as well as fauvism, impressionism, expressionism and other modernist movements, Biss pushed himself and his friends to create an entirely new genre that we know today as Contemporary Southwestern Art. ‘Earl was the catalyst,’ Red Star said, ‘like the agitator in a washing machine.’

Biss went on to the San Francisco Art Institute on a full scholarship, then moved to Paris where he haunted museums and studied printmaking with S. W. Hayter. Returning to Santa Fe, he rented studio space with several of his fellow artists who continually pushed each other to further develop their unique styles.

Even as his career skyrocketed, Earl’s struggle with his dark side intensified. He painted in bursts of 48 or even 72 hours, refusing to eat and working to collapse. When not in the studio, he was famous for his consumption of alcohol and other substances, and for going through nine marriages.

Weakened both by his lifestyle and a childhood bout with rheumatic fever that damaged his heart, Earl Biss died of a stroke in his studio in 1998. His works in the Contemporary Southwestern Art style are now collected worldwide.